This page will contain selected solutions and discussion based on exercises from the book Geometry and Topology by Miles Reid and Balázs Szendrői. The preface and an excerpt from the first chapter is available at the official website, and physical copies are available in university libraries throughout the UK. The book also forms the basis for the University of Warwick second year undergraduate mathematics course MA243 Geometry.

Appendix A on Metrics

See the Wikipedia articles on Metric Spaces and Metrics for definitions and further background. An interactive tool for visualising a unit ball in $\mathbb{R}^{2}$ with respect to various standard metrics is given here.

Exercise A.1

Suppose $X$ is a metric space, and $t : X \to X$ is a distance preserving map. Then $t$ is an injective function.

However, $t$ need not be a bijective function, since it may fail to be surjective. For example, consider the set of integers $\mathbb{Z}$ together with the discrete metric: $$d(n,m) = \delta_{n,m} = \begin{cases} 0 & \text{if }n = m, \\ 1 & \text {if }n \neq m.\end{cases}$$ Then the doubling map $t(n) = 2n$ is distance preserving with respect to this metric, but its image is the strict subset $2\mathbb{Z} \subsetneq \mathbb{Z}$.

Thus it is possible for an (infinite) metric space to be isometric to a strict subset of itself. This is analogous to the fact in set theory that an infinite set can be in bijection with a strict subset of itself.

In fact any set is a metric space with respect to the discrete metric, and injective maps between metric spaces using the discrete metric are distance preserving since they separate (distinct) points.

A vivid description of such maps between infinite sets dates back to 1924 with Hilbert’s paradox of the Grand Hotel. Here is an article which describes the idea with a couple illustrations and some accompanying history.

Exercise A.2

Let $S = \{1,\ldots,n\}$ be a set containing $n$ elements, and $X = \mathcal{P}(S)$ the set of all subsets of $S$, also known as the power set of $S$. For $x,y \in X$, the rule $d(x,y) = |x \triangle y|$ defines a metric on the set $X$, where $x \triangle y$ denotes the symmetric difference of $x$ and $y$ (the set of elements of $S$ contained in exactly one of $x$ or $y$ but not both), and we take the size of the resulting set.

The main thing to check is that the triangle inequality is satisfied, and this follows from the inclusion $A \triangle C \subset (A \triangle B) \cup (B \triangle C)$. This can be proven using (abelian) group properties of power sets with symmetric difference (associativity, empty set as neutral element, and every set is its own inverse) together with the fact $A \triangle B = (A \cup B) \setminus (A \cap B) \subset A \cup B$ to find that $$A \triangle C = (A \triangle B) \triangle (B \triangle C) \subset (A \triangle B) \cup (B \triangle C).$$ Moreover, this shows that the triangle equality is an equality if and only if $A \triangle B$ and $B \triangle C$ are disjoint sets, where $(A \triangle B) \cap (B \triangle C) = (B \setminus (A \cup C)) \sqcup ((A \cap C) \setminus B)$.

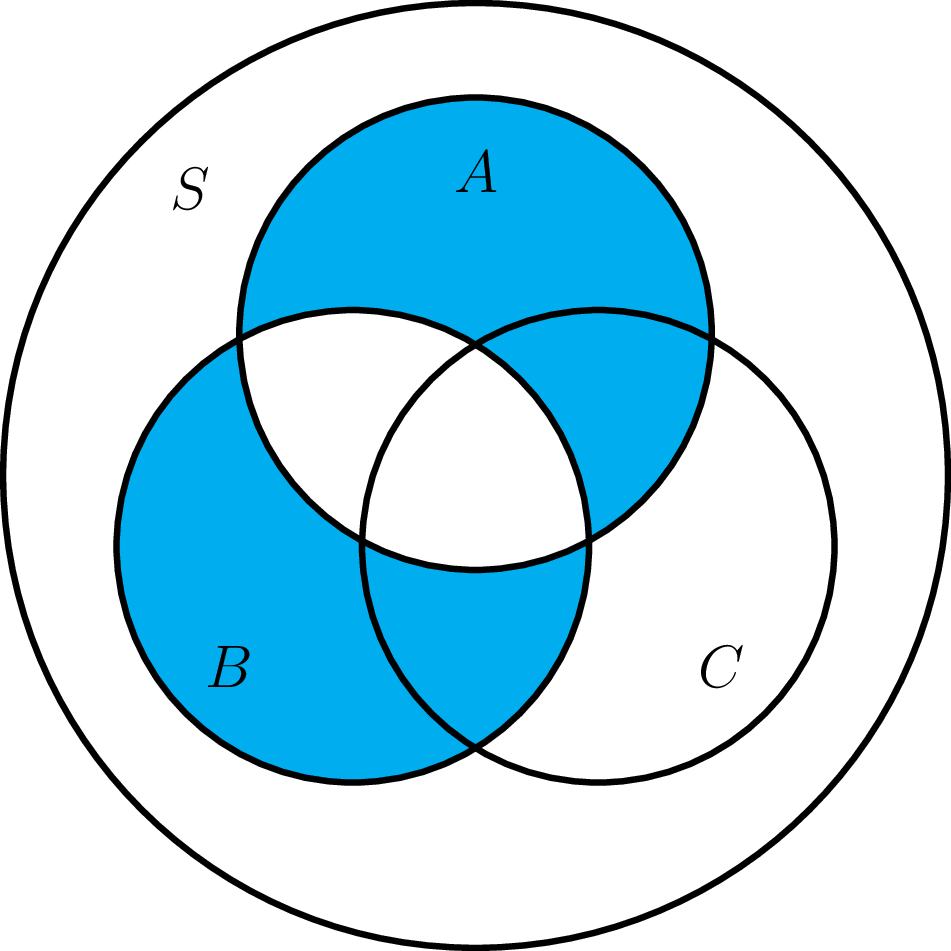

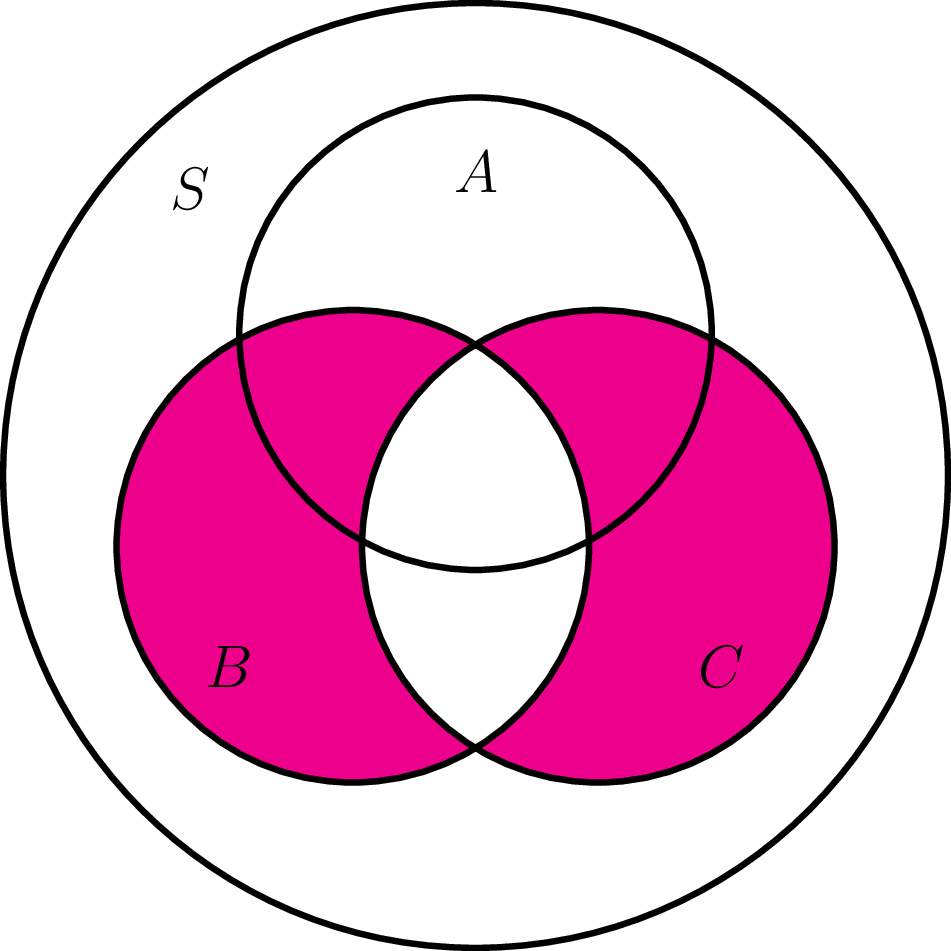

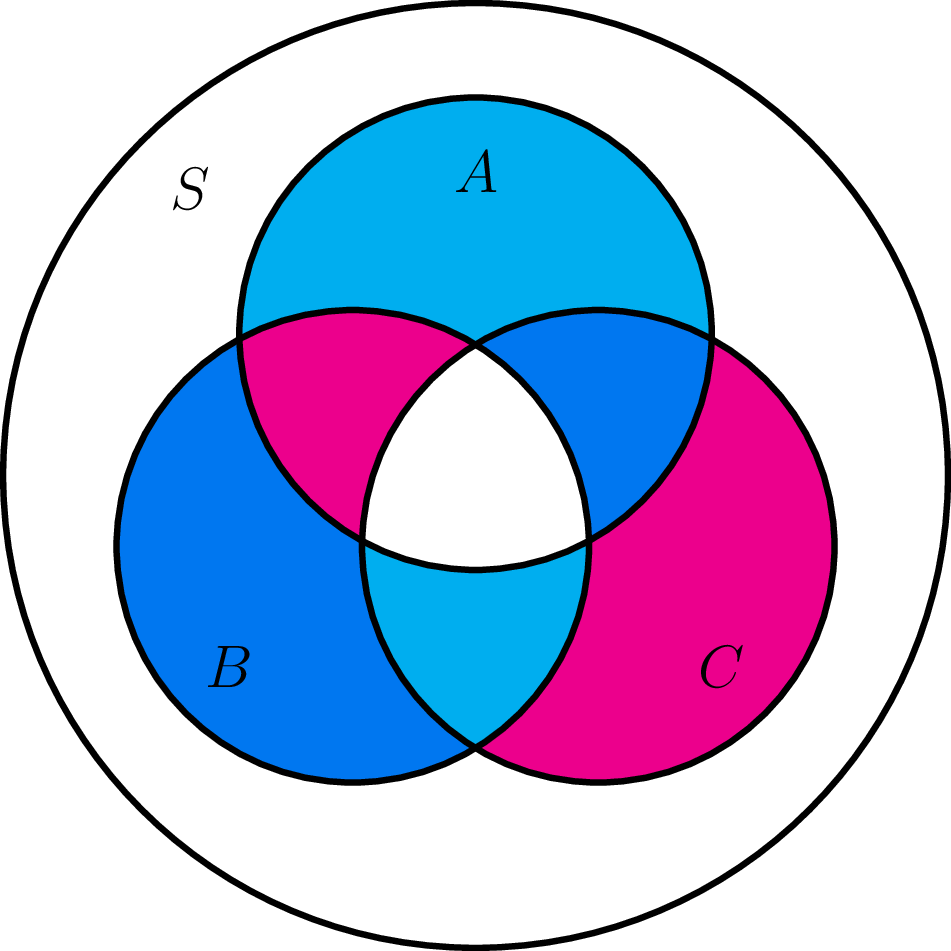

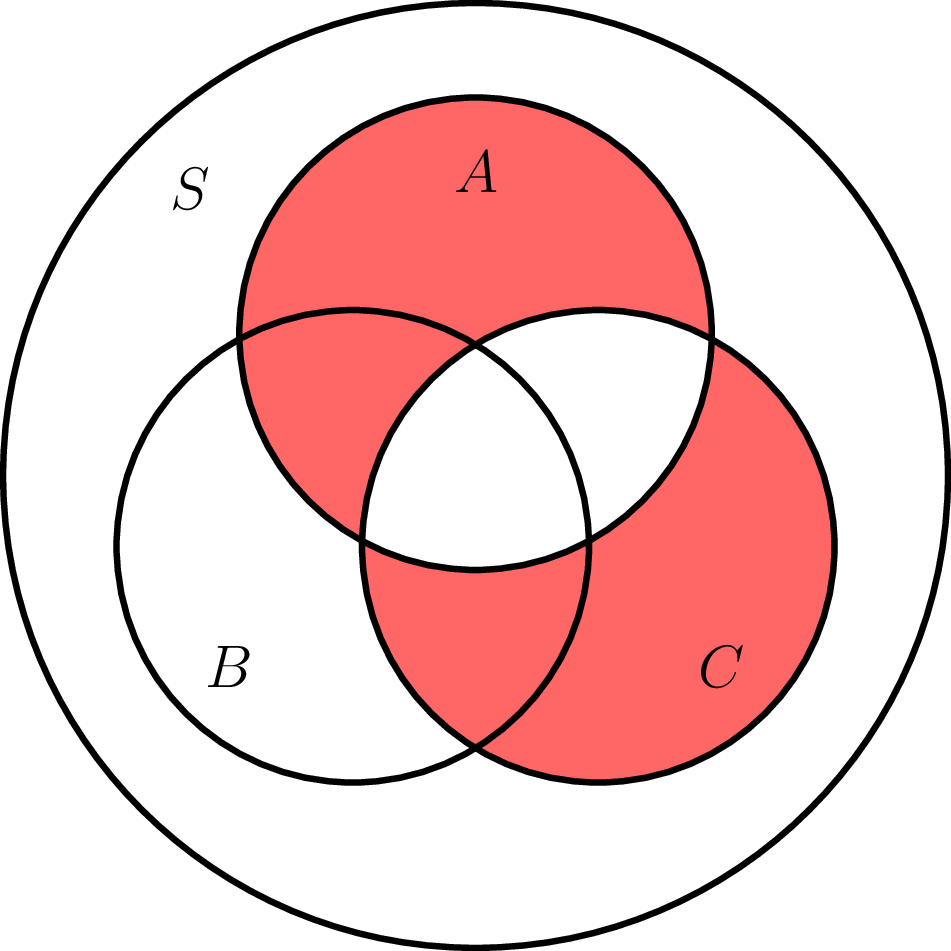

Alternatively, we can observe from the following arrangement of Venn diagrams that $$|A \triangle B| + |B \triangle C| = |A \triangle C| + 2|B \setminus (A \cup C)| + 2|(A \cap C) \setminus B| \ge |A \triangle C|.$$

See the following three links for how to produce your own Venn diagrams.

The metric space $(X,d)$ is equivalent to the set of binary strings of length $n$ with the Hamming distance. This can be seen by identifying the inclusion (or not) of an element $i$ in a subset $A \subset S$ with the value of the symbol ($1$ or $0$, respectively) at index $i$ in the corresponding string. Then the symmetric difference of sets corresponds to the XOR operation on binary strings, and the size of the resulting set is equal to the number of ones (population count) of the resulting string.

Hamming distance and the related notion of Hamming weight have applications in information theory, coding theory, and cryptography, such as error correction and detection in electronic communications.

If $S$ was instead an infinite set then the construction $d(x,y) = |x \triangle y|$ would fail to be a metric on $X = \mathcal{P}(S)$ since the function $d$ could take on infinite values whilst metrics are required to return values in $\mathbb{R}_{\ge 0}$. However, if we define $X$ to consist of only finite subsets of $S$, then $(X,d)$ would once again constitute a metric space. Whereas before the distance between points in $X$ was bounded above by $n = |S|$, when $S$ is infinite there is no upper bound on the size of $x \triangle y$ for arbitrary finite subsets $x,y \subset S$.

Compare and contrast with the Levenshtein distance between strings (which need not have the same length), which is determined by the minimum number of single-character edits (insertions, deletions or substitutions) required to change one string into the other. This differs from our symmetric difference-based metric (on $S = \mathbb{N}$) because when comparing strings of different length, there is a predetermined method for extending the shorter string to match the length of the longer one (by padding on the right with $0$'s), then we compare them as two strings of equal length with XOR followed by a population count.

Exercise A.3

Let $P$ be the set of polynomials in one variable with coefficients in $\mathbb{Z}/2$, i.e. $P = \mathbb{Z}/2[x]$. Then the difference $f - g$ between two polynomials $f,g \in P$ acts as the XOR operator on their coefficients, and defining $d(f,g)$ to be the number of nonzero terms in the difference $f - g$ gives a metric on $P$. Moreover $(P,d)$ is isometric to the set $X$ of finite subsets of $\mathbb{N}$ with the metric $d_{X}(x,y) = |x \triangle y|$ for $x,y \in X$. The isometry can be realised by mapping $$f = \sum_{i=0}^{n} a_{i} x^{i} \mapsto \{ i \in \mathbb{N} | a_{i} \ne 0 \} \in X.$$

This highlights the $\mathbb{Z}/2$-vector space structure on $X$ induced by the symmetric difference, from which we can see that $d$ is a metric induced from a norm.

Exercise A.4

Prove that a metric space with exactly 3 points is isometric to a subset of $\mathbb{E}^{2}$.

A metric space with exactly 3 points can be described completely by 3 pieces of data, namely the distances between the points (making use of symmetry and $d(x,x)=0$). Let $(M,d)$ be our metric space with $M = \{A,B,C\}$ and write $a = d(B,C)$, $b = d(A,C)$, $c = d(A,B)$. By renaming/reordering the points if necessary, we can assume that the lengths satisfy $0 < b \le a \le c$. With this assumption, the only nontrivial restriction imposed by the triangle inequality is $c \le a + b$.

Now it suffices to find an isometry from $M$ into $\mathbb{R}^{2}$. This will realise $M$ as a (possibly degenerate) triangle in $\mathbb{R}^{2}$. A corollary of the statement is the classic result that a triangle in $\mathbb{E}^{2}$ is uniquely determined (up to congruence) by the lengths of its three sides.

In the diagram below, we illustrate how the assumption on the ordering of lengths we made above restricts the configuration of points when mapped into $\mathbb{R}^{2}$.

We describe a map $f : M \to \mathbb{R}^{2}$ which yields the desired isometry. Let $f(A) = (0,0)$ and $f(B) = (c,0)$ so that $d(f(A),f(B)) = c$. Then to complete the isometry we require $f(C) = (x,y)$ where $x,y \in \mathbb{R}$ are such that $x^{2} + y^{2} = b^{2}$ and $(c - x)^{2} + y^{2} = a^{2}$. A solution to this pair of equations is given by $x = \frac{1}{2}(c - \frac{a^{2} - b^{2}}{c})$, $y = \sqrt{b^{2} - x^{2}}$.

To ensure that $y$ is a well-defined real number it suffices to show that $b^{2} - x^{2} \ge 0$. The formula $$x = \frac{1}{2}(c - \frac{a^{2} - b^{2}}{c}) = \frac{b^{2} + (c^{2} - a^{2})}{2c}$$ ensures that $0 < \frac{b^{2}}{2c} \le x \le \frac{c}{2}$, recalling the ordering of lengths $0 < b \le a \le c$. Then factoring $b^{2} - x^{2} = (b + x)(b - x)$ we see that $b + x > 0$ , so it is enough to show that $b - x \ge 0$.

Now consider $$b - x = \frac{2bc + a^{2} - b^{2} - c^{2}}{2c} = \frac{a^{2} - (b - c)^{2}}{2c} = \frac{(a + b - c)(c + (a - b))}{2c} \ge 0$$ since $0 < b \le a \le c \le a + b$ so all factors on the right hand side of the equation are positive.

Exercise A.5

Let $X = \{A,B,C,D\}$ with $d(A,D) = 2$ and $d(P,Q) = 1$ for all $P,Q \in X$ such that $P \neq Q$ and $\{P,Q\} \neq \{A,D\}$. Then $d$ describes a metric on $X$ (in particular, $d$ satisfies the triangle inequality), but the metric space $X$ is not isometric to any subset of $\mathbb{E}^{n}$ for any $n$.

Suppose, for contradiction, we had $f : X \to \mathbb{R}^{n}$ giving an isometry from $X$ to a subset of $\mathbb{R}^{n}$ (and hence by extension $\mathbb{E}^{n}$) for some $n$.

Since $A$, $B$, $D$ satisfy the triangle inequality with equality: $d(A,D) = d(A,B) + d(B,D) = 2$, and $f$ is an isometry into $\mathbb{R}^{n}$, we may apply the triangle inequality theorem for $\mathbb{R}^{n}$ (equality case) to deduce that $f(A)$, $f(B)$, and $f(D)$ are collinear. In particular, $f(B)$ lies on the line segment between $f(A)$ and $f(D)$, and we can write $f(B) = f(A) + \lambda(f(D) - f(A))$ for some real number $\lambda \in [0,1]$. Then $\lambda = \frac{|f(B) - f(A)|}{|f(D) - f(A)|} = \frac{d(A,B)}{d(A,D)} = \frac{1}{2}$, and so $f(B) = \frac{1}{2}(f(A) + f(D))$.

However, the same argument applies to $A$, $C$, $D$ to show that $f(C) = \frac{1}{2}(f(A) + f(D))$. Therefore $|f(C) - f(B)| = 0 \neq 1 = d(B,C)$ which contradicts the assumption that $f$ is an isometry, so no such $f$ can exist.

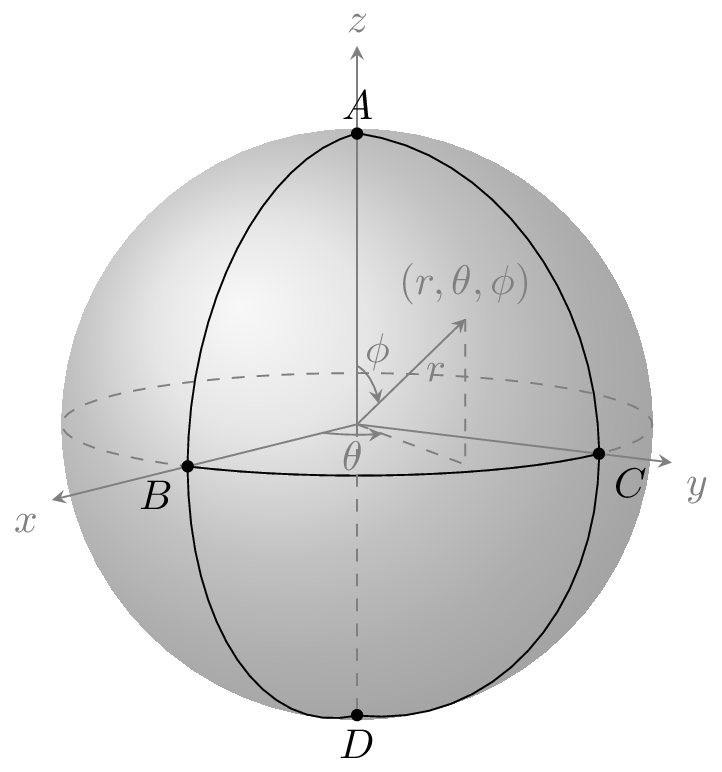

However, we can realise $X$ as a subset of the sphere $S^{2}$ of radius $\frac{2}{\pi}$ with the spherical great circle metric as follows:

In spherical coordinates $(r,\theta,\phi)$, we can describe an isometry with $X$ by choosing $$A = (\frac{2}{\pi},0,0), B = (\frac{2}{\pi},0,\frac{\pi}{2}), C = (\frac{2}{\pi},\frac{\pi}{2},\frac{\pi}{2}), D = (\frac{2}{\pi},0,\pi).$$

Alternatively, by embedding the sphere in $\mathbb{R}^{3}$, this is equivalent in Cartesian coordinates $(x,y,z)$ to $$A = (0,0,\frac{2}{\pi}), B = (\frac{2}{\pi},0,0), C = (0,\frac{2}{\pi},0), D = (0,0,-\frac{2}{\pi}).$$

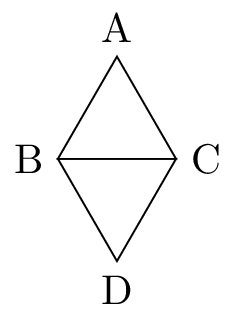

It is also possible to realise $X$ isometrically as a graph, as shown below. We can give any connected graph a metric space structure by defining the distance between two vertices to be the length of the shortest path between them. In particular, the distance between vertices connected by an edge is $1$.